FAIR Data Digest #9

Podcast Pick: Jimmy Wales about Wikipedia | Data Integration with TheFuzz (Python) | Introducing ESFRI

Hi everyone,

greetings to one of our summer editions! Whether you're on vacation, just back, or about to head off, I've got some interesting content to share with you. Check out a super intriguing podcast episode, stay updated with a work-related highlight, and of course, join in the fun with another edition of FAIR Buzzword Bingo.

🎙️ Ever pondered the inception and significance of Wikipedia in today's world, especially in the era of AI and ChatGPT? Delve into the intriguing story with co-founder Jimmy Wales as he shares his insights on the Lex Fridman podcast.

❓ Ever wondered what unfolds when a collaborative force of 1,000 scientists put their heads together, while 200 others rigorously peer-review it? A game-changing strategy that influences research across various fields! In this edition, I'll delve into the remarkable European Strategy Forum on Research Infrastructures (ESFRI), which kicked off two decades ago and has since brought us numerous infrastructures—some of which I've introduced in previous editions. I'll provide background insights, shine a spotlight on the Social Sciences and Humanities (SSH) , and of course, focus on FAIR data.

🏢 Integrating data from diverse sources can be quite a challenge, especially when common identifiers are absent. Recently, I tackled this obstacle by employing the Python library, TheFuzz, to match thousands of Persons from the Unesco Index Translationum database to our BELTRANS project database. Thanks to string similarity algorithms, the process was made smoother and more efficient! I'll share further details in my work update, so stay tuned for that!

🎙️ Podcast Picks

According to Wikipedia, Wikipedia is “an online encyclopedia written and maintained by a community of volunteers, known as Wikipedians” (source). It was built 22 years ago by Jimmy Wales (Q181) and Larry Sanger (Q185).

It is an amazing project and I can’t imagine a world without it. The worlds knowledge is literally at your fingertips! Recently, Jimmy Wales was on the Lex Fridman podcast (Q109248984) where he gave a 3 hours interview. They talked about the origin of Wikipedia, its design, ChatGPT, conspiracy theories, Wikipedia’s funding and many more topics.

I found it super interesting and can only recommend it to you! Don’t worry, there are also timestamps to navigate through the interview and in some podcast players they are clickable. And if you are more of a text person, no problem. Via the Wikidata page of this episode (Q119709210) I found its transcript that you can check out here.

❓ FAIR Buzzword Bingo: ESFRI

There are already countless intertwined research and infrastructure initiatives in the cultural heritage field, even more beyond it. Each week I will focus on one of the many FAIR data-related initiatives; last week I looked at DARIAH / CLARIAH; this week one of the most fundamental ones: the European Strategy Forum on Research Infrastructures (ESFRI). I will give some general background, details on the Social Sciences and Humanities (SSH) part of it, why you should care and of course how it all relates to FAIR data.

Systematically publishing FAIR data involves a great deal of setting up sustainable research infrastructures. This does not come overnight, there needs to be strategic planning, coordination and money. In a previous edition I introduced ERICs, legal entities according to European law focusing on the establishment and operation of research infrastructures. And we have seen concrete ERICs such as DARIAH-ERIC. But who came up with the idea of ERICs in the first place? Today I want to introduce ESFRI, an initiative that defines and monitors a strategic roadmap of research infrastructures since 20 years!

In short, ESFRI (Q2623454) was set up with a mandate from the EU Council in 2002 to develop the scientific integration of Europe and to strengthen its international outreach. Since then the scientific quality, open access and collaboration have been corner stones of ESFRI. It consists of different working groups that cover different scientific domains. Whereas some domains rely on heavy physical infrastructure others rely more on digital infrastructure and collaboration. The proposal to establish legal entities for research infrastructures (which became ERIC) also came from ESFRI by the way.

Over the years different roadmap reports were published, namely in 2006, 2008, 2010, 2016 and 2021. In the first roadmap, 35 initiatives were presented among which CLARIN (FAIR Data Digest #7) and DARIAH (FAIR Data Digest #8). In each follow-up roadmap report the status of those initiatives is checked. If such an initiative reached the implementation phase it becomes an ESFRI landmark. However, initiatives may also be removed from the roadmap. Currently there are 22 projects and 41 landmarks, thus 61 initiatives in total.

Social Sciences and Humanities (SSH)

I think the following quote from the ESFRI Roadmap 2006 explains at least the humanities part nicely.

“Just like astronomers require a virtual observatory to study the stars and other distant objects in the galaxy, researchers in the humanities need a digital infrastructure to digitise, get access to and study the sources that are until now hidden and often locked away in cultural heritage institutions. Much of the source material so vital to humanities is scattered across libraries, archives, museums and galleries, and as yet only a fraction is available in a digital form.” - ESFRI Roadmap 2006

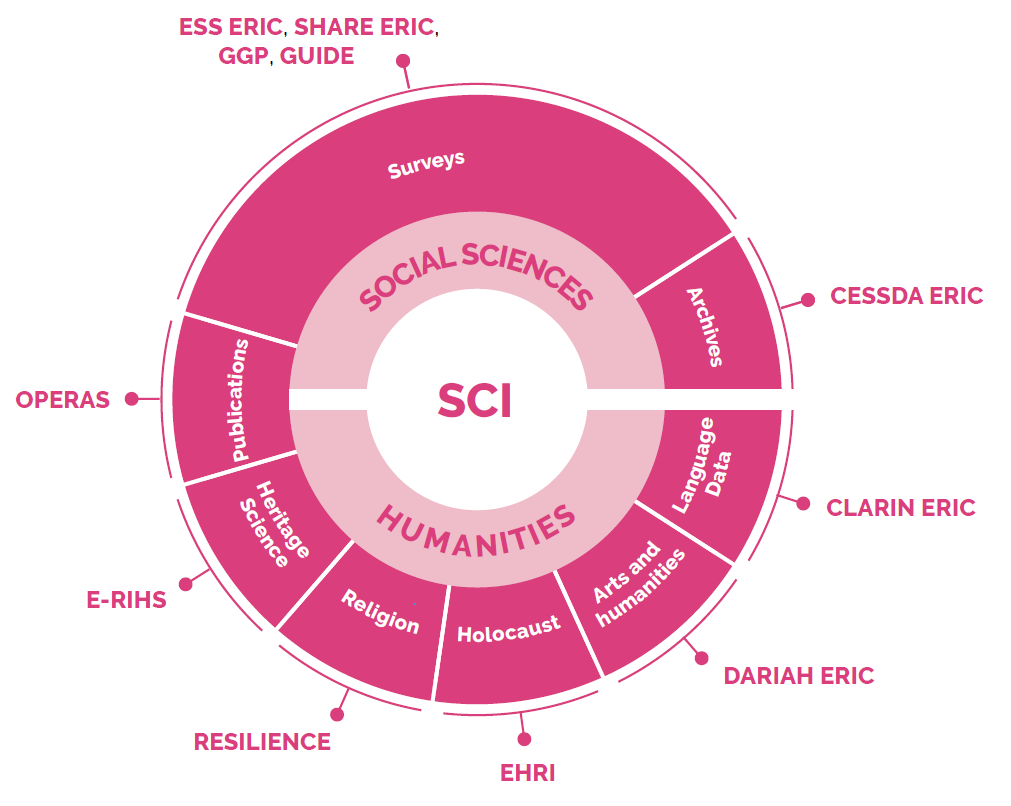

Already in the 2010 Roadmap, the Joint Programming Initiative on Cultural Heritage and Global Change called for "closer cooperation with research infrastructures in the social sciences and humanities". Below you will see an image of current projects and landmarks of this domain from the ESFRI Roadmap 2021.

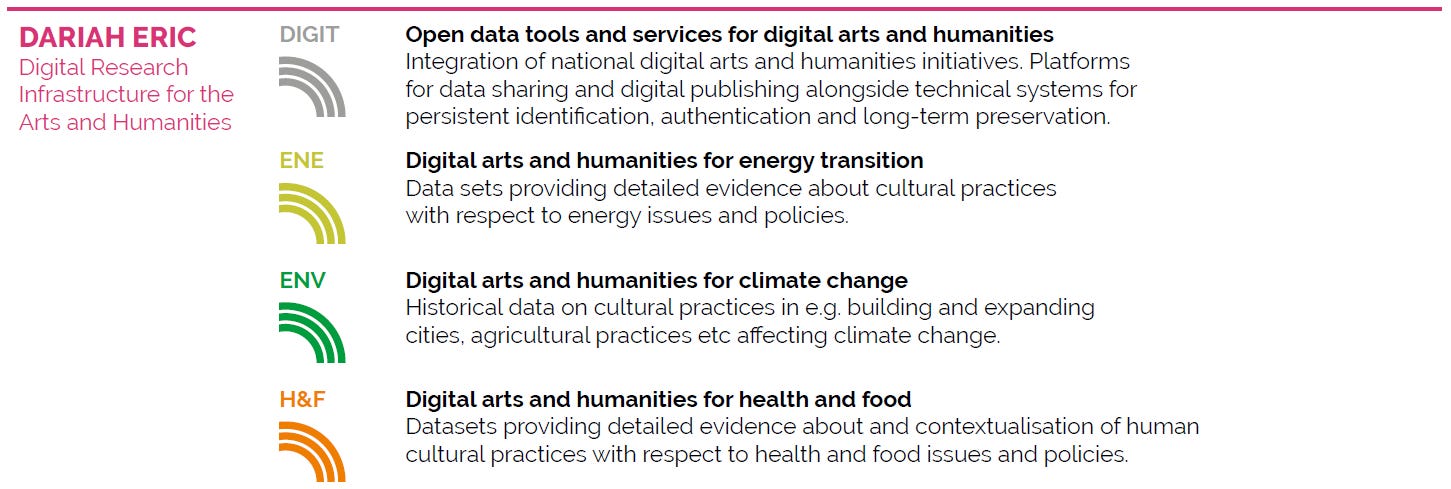

But there are not only links between Social Sciences and Humanities. There are also links across ESFRI disciplines. Check out the following example of how the DARIAH-ERIC relates to the ESFRI fields of Data and Computing (DIGIT), Energy (ENE), Environment (ENV) and Health and Food (H&F).

More information on the current state of all the research infrastructures and how they relate to each other you can check out in the ESFRI roadmap of 2021.

Why should you care?

First of all, in this century, it is no longer beneficial for science to take place in ivory towers. There has to be collaboration. And especially for digital matters and FAIR data, we do not want data silos, there has to be some kind of coordination.

If you are in science (and I know that some of the readers are), roadmaps like ESFRI provide you with the opportunity to use research infrastructures in the first place. But it also allows you to position your own projects in a larger context.

Each EU member state may participate in different ESFRI initiatives and it depends on the country how this happens. For example, the ESFRI page for Belgium links to a document of the Flemish government (in English) that explains the situation. Each entity in the federalism of Belgium is independent with its own governance model and research funding programmes and can therefore participate in international research. “The decision on these participations is consolidated in the commission for international cooperation and confirmed by the inter-ministerial conference”.

An overview of all the Belgian participations is listed under the following page of the Belgian Science Policy Office (BELSPO).

ESFRI and FAIR data

The most important question for this newsletter: how about FAIR data? The FAIR principles were officially described in 2016. It is interesting that the need for something like FAIR data was already expressed in the 2006 and 2010 roadmaps as you can see in the following quotes.

“The answers to these challenges should focus on the need for European‑wide data, interoperability of data and languages to harmonisation of data access policies, the standardisation of digitation processes as well as interoperability between the humanities and the social sciences in general.” - ESFRI Roadmap 2006

And in 2010 there was a specific statement with respect to e-Infrastructues.

“Across all research areas, e-Infrastructures are playing an ever increasing role in data acquisition and management, digital repositories, access to standardised, calibrated and inter-operable data, data curation, the mining of archived data and its release for broad access. Data taking and data management is something that is often overlooked at the beginning of a Research Infrastructure project, as is the financing of the necessary e-Infrastructures.” - ESFRI Roadmap 2010

In the most recent roadmap of 2021 FAIR principles are explicitly mentioned.

"However, many aspects remain to be improved to further consolidate the European RI landscape. For instance, there is still a need for an interoperable data system that fully complies with the FAIR principles and is well integrated into a functioning EOSC ecosystem serving the needs of the European research communities" - ESFRI Roadmap 2021

Thus, there is a recognized need for FAIR data, and that is very important! The last quote also makes the link to the European Open Science Cloud. An initiative that I will present in a future edition.

What do you think about ESFRI, are you involved and how are your experiences? Please let me know if I’ve missed something important!

🏢 Work updates

When data is not fully FAIR you have to do some more effort to get the value out of it. A very typical problem nowadays is data integration: combining data from different sources.

In the BELTRANS research project (Q114789456), we integrate metadata of book translations from various data sources. Even though most data sources are FAIR to a certain extent, some only provide textual information.

The online database Index Translationum from Unesco is such an example. You can retrieve somewhat structured information about book translations (check this Python script to scrape content), but there are no identifiers for authors or translators.

So the problem is to match thousands of person names of Unesco with our project database. We do this in two steps: first find possible name matches based on name similarity, and second, for each candidate we find, we check if they have at least x book titles in common.

The problem is that there might be different spellings or small typos in the names. For example, instead of “Hugo Claus” it could be “Claus, Hugo” or “Hugu Claus”. Different algorithms exist to measure the similarity of two pieces of texts (two strings), to say, for example, if two strings are 95% similar or only 70%.

Long story short, we used the Python library TheFuzz which provides several implementations of string similarity algorithms. In particular, the token_sort_ratio function achieved the best results in our case and I will tell you why.

It should become clear when you check the following examples of the documentation.

>>> fuzz.ratio("fuzzy wuzzy was a bear", "wuzzy fuzzy was a bear")

91

>>> fuzz.token_sort_ratio("fuzzy wuzzy was a bear", "wuzzy fuzzy was a bear")

100As you can see in this example, the token_sort_ratio provides a clear match whereas the ratio function only detects a 91% similarity. This is because the token_sort_ratio function takes a different sorting of words into account. And especially in our case we often have person names that are either of the pattern “firstname lastname” or “lastname, firstname”.

Using this approach we could already match more than 3,000 persons automatically and integrate them with the rest of our database.

That’s it for this week of the FAIR Data Digest. Let me know what you think about the content or if I have missed something. Don’t forget to share or subscribe. See you next week!

Sven